The past weeks have seen a massive confrontational movement arise in France opposing President Emmanuel Macron’s “ecological” tax increase on gas. This movement combines many contradictory elements: horizontally organized direct action, a narrative of being “apolitical,” the participation of far-right organizers, and the genuine anger of the exploited. Clearly, neoliberal capitalism offers no solutions to climate change except to place even more pressure on the poor; but when the anger of the poor is translated into reactionary consumer outrage, that opens ominous opportunities for the far right. Here, we report on the yellow vest movement in detail and discuss the questions it raises.

A las barricadas: the yellow vest movement has provided a venue for people to revolt without giving up their identity as consumers.

Preface: The Ruling Center and the Rebel Right

In the buildup to the 2018 elections in the US, we heard a lot of arguments that it would be better for centrist politicians to win control of the government. But what happens when centrists come to power and use their authority to stabilize capitalism at the expense of the poor? One consequence is that far-right nationalists gain the opportunity to present themselves as rebels who are trying to protect “ordinary people” from the oppressive machinations of the government. In a time when the state can do precious little to mitigate the suffering that capitalism is causing, it can be more advantageous to be positioned outside the halls of power. Consequently, far-right nationalism may be able to gain more ground under centrist governments than under far-right governments.

In attempting to associate environmentalism, feminism, internationalism, and anti-racism with neoliberalism, centrists make it likely that at least some of the movements that arise against the ruling order will be anti-ecological, misogynistic, nationalistic, and racist. That works out well for centrists, because it enables them to present themselves to the world as the only possible alternative to far-right extremists. This is precisely the strategy that got Macron elected in his campaign against Marine Le Pen. In this regard, centrists and nationalists are loyal adversaries who seek to divide up all possible positions between themselves, making it impossible to imagine any real solution to the crises created by capitalism.

A social movement of anger and confusion.

In short: if the wave of nationalist victories still sweeping the globe eventually gives way to a centrist backlash, but anarchists and other revolutionaries are not able to popularize tactics and movements that adequately address the catastrophies that so many people are facing, that could pave the way for an even more extreme wave of far-right populism.

We should study populist social movements under centrist governments in order to identify the ways that far-right groups can hijack them—and figure out how we can prevent that. This is one of the reasons to pay close attention to the “yellow vest” movement unfolding right now in France under the arch-centrist President Macron.

The “yellow vest” movement shows the strange fractures that can open up under the contradictions of modern centrism: above all, the false dichotomy between addressing global warming and addressing the ravages of capitalism. This dichotomy is especially dangerous in that it gives nationalists a narrative with which to capitalize on economic crisis while discrediting environmentalism by associating it with state oppression.

Against the dictatorship of the rich: a banner seen near Nantes.

What is taking place in France is reminiscent of what happened in Brazil in 2013, when a movement against the rising cost of public transportation provoked a nationwide crisis. This crisis gave tens of thousands of people new experience with horizontal organizing and direct action, but it also opened the way for nationalists to gain ground by presenting themselves as rebels against the ruling order. There are two significant differences between Brazil in 2013 and France today, however. First, the movement in Brazil was initiated by anarchists, but grew too big too quickly for anarchist values to retain hegemony—whereas anarchists have never had leverage within the movement of the “yellow vests.” Second, the movement in Brazil took place under a supposedly leftist government, not a centrist one. The hijacking of the movement against the fare hike in Brazil set the stage for a chain of events that culminated in the electoral victory of Bolsonaro, an outright proponent of military dictatorship and extrajudicial mass murders. In France, the context seems even less promising.

What should anarchists do in a situation like this? We can’t side with the state against demonstrators who are already struggling to survive. Likewise, we can’t side with demonstrators against the natural environment. We have to establish an anti-nationalist position within anti-government protests and an anti-state position within ecological movements. The “yellow vest” movement provides an instructive opportunity for us to think about how to strategize in an era of three-sided conflicts that pit us against both nationalists and centrists.

Burning barricades.

The Yellow Vest Movement in France

Several weeks ago, the Macron government officially announced that, on January 1, 2019, it will once again increase taxes on gas, which will raise the price of gas in general. This decision was justified as a step in the transition to “green energy.”

Diesel vehicles comprise two thirds of vehicles in France, where diesel is less expensive than regular gas. After decades of political policies aimed at pushing people to buy cars that run on diesel, the government has decided that diesel fuels are no longer “eco-friendly” and therefore people must change their cars and habits. Macron reduced taxes on the income of the super-rich at the beginning of his administration; he has not taken steps to make the wealthy pay for the transition to more ecologically sustainable technology, even though the wealthy have been the ones to benefit from the profits generated by ecologically harmful industrial activity. Consequently, Macron’s ecological arguments for the gas tax been largely ignored. Many people see the decision to increase the tax on gas as yet another attack on the poor.

The French government is responsible for creating this false dichotomy between ecology and the needs of working people. Decades of spatial planning have concentrated economic activity and job opportunities in bigger metropolises and developed public transportation in those same areas while isolating rural areas, making cars necessary for a large part of the population. Without any other option, many people are now completely reliant on their cars to live and work.

Blocking a toll collection point.

In response to Macron’s announcement about the tax on gas, people started organizing on the internet. Several petitions against the increase of the price of gas became viral, such as this online petition that is about to reach a million signatures as this text goes to press. Then, on September 17, 2018, a driver organization denounced the “overtaxation of fuels,” inviting its members to send their gas receipts to President Macron along with letters explaining their disapproval. On October 10, 2018, two truck drivers created a Facebook event calling for a national blockade against the increase of gas prices on November 17, 2018. As a result, more and more groups appeared on Facebook and Twitter sharing videos in which people attack the president’s decision and explain how difficult their financial situations already are, emphasizing that increasing the taxes on gas will only make it worse.

On the eve of the national call, about 2000 groups across the country were announcing their intention to block roads, toll collection points, gas stations, and refineries, or at least to hold demonstrations.

In order to identify the participants during this day of action, demonstrators decided to wear yellow emergency vests and asked sympathizers to show their support to the movement by displaying these vests in their cars. The symbolism behind this vest is simple enough. The French driver’s manual mandates that every driver must keep an emergency vest inside their car in case of accident or other issues on the road. In view of their dependency on cars, fearing to see their living conditions worsen, protestors chose these emergency vests as a symbol of resistance against Macron’s decision. By extension, protestors and media came to call this movement the “yellow vests.”

A blockade near Nantes on November 17.

Thousands of actions took place during the weekend of November 17. Approximately 288,000 “yellow vest” protestors were present in the streets for the first day of national blockade. This was a success for the movement, especially considering that it did not receive any assistance from trade unions or other major organizations.

Unfortunately, things escalated when fights broke out between “yellow vests” and other individuals. One “yellow vest” protester, a woman in her sixties, was killed by a driver, a mother who was trying to take her sick child to the doctor and attempted to drive through a blockade when people in yellow vests started smacking her car. Altogether, more than 400 people were injured, one protestor was killed, and about 280 individuals were arrested that weekend.

The movement remained strong despite these incidents. The blockades continued over the following days, even if participation diminished. In order to maintain the pressure on the government, the “yellow vests” made another national call for the following Saturday, November 24. Once again, various “yellow vest” groups on Facebook planned actions and demonstrations everywhere in France and circulated a call to converge in Paris for a big demonstration.

Protesters facing a water cannon. The image looks heartening, but the far-right nationalist Action Française claims that the picture shows their militants “forming the front line against the forces of order.”

At first, this demonstration was planned for the Champs de Mars, near the Eiffel tower, where law enforcement would have surrounded and contained the protestors. However, this official decision did not satisfy some “yellow vesters,” and other calls circulated on social media. The November 17 demonstration in Paris had failed to reach its objective, the Presidential palace; consequently, the “yellow vesters” who were about to converge in Paris decided to repeat that effort on November 24. So it was that, rather than gathering at the base of the Eiffel tower, people converged and blocked the Champs Elysées, a target with powerful symbolic status. This luxurious avenue is the most visited in Paris; the Elysée palace where President Macron resides is located at the end of this avenue.

As they had the preceding week, demonstrators tried to get as close to the Presidential palace as possible. Barricading and confrontations took place all day along the most well-known Parisian avenue. It was reported that this second round of actions gathered about 106,000 participants throughout France, with about 8000 in Paris. These figures suggest that the movement is losing momentum. In the course of the demonstration in Paris, 24 people were injured in clashes and 103 people were arrested, of whom 101 were taken into custody. The first trials took place on Monday, November 26.

Bonfire on the Champs Elysées.

What Kind of Movement Is This?

The “yellow vest” movement describes itself as spontaneous, horizontal, and without leaders. It is difficult to be certain of these statements. The movement started via social media groups that facilitated decentralized actions in which people decided locally what they wanted to do and how to do it. In this regard, there is clearly some kind of horizontal organizing going on.

Regarding whether the movement is truly leaderless, this is more complicated. From the beginning, “yellow vesters” insisted that their movement was “apolitical” and had no leader. Instead, it was supposed to be the organic effort of several groups of people working together on the basis of their shared anger.

Nevertheless, as in practically every group—anarchist projects included—there are power dynamics. As is often the case, some people manage to accumulate more leverage than others, due to their access to resources, their capacity to persuade, or simply their skills with new technologies. Scrutinizing some of the self-proclaimed spokespersons of the “yellow vest” movement, we can see who has been able to accumulate influence within the movement and consider what their agenda might be.

-

Christophe Chalençon is the spokesperson for the Vaucluse department. Presenting himself as “apolitical” and “not belonging to any trade union,” he nevertheless presented his candidacy for the 2017 legislative election as a member of the “diverse right.” When we dig deeper into his personal relations and Facebook profile, we can see that his discourse is clearly conservative, nationalist, and xenophobic.

-

In Limoges, the organizer of the November 17 action of the “yellow vests” in the region was Christophe Lechevallier. Once again, the profile of this “angry citizen” is quite interesting. The least we can say is that Christophe Lechevallier seems to be a turncoat. In 2012, he presented his candidacy for the legislative elections as a member of a centrist party (the MoDem). Then he joined the extreme-right Front National (now called the Rassemblement National) and invited in 2016 its leader Marine Le Pen to a meeting. In the meantime, he was also working with the French pro-GMO agricultural organization FNSEA (the National Federation of Agricultural Holders’ Unions), known for defending the use of chemicals, such as the Glyphosate, to intensify their productions.

-

In Toulouse, the “yellow vest” spokesperson is Benjamin Cauchy. This young executive has been interviewed several times on national and local media. Again, this spokesperson is hardly “apolitical” if we consider his past. Benjamin Cauchy speaks freely about his political experience as a member of the traditional neoliberal right (at that time, the UMP, now known as Les Républicains). However, during law school, Benjamin Cauchy was one of the leaders of the student union UNI—well-known for its connections with conservative right and far-right parties and groups. But even more interesting, Benjamin Cauchy has not publicly acknowledged that he is now a member of the nationalist party Debout La France, whose leader, Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, made an alliance with Marine Le Pen (of the Rassemblement National) during the second round of the last presidential election in hopes of defeating Macron.

There are frustrated consumers on both sides of the barricades.

So it is clear that conservative and far-right groups are hoping to impose their discourse, spread their ideas, and use this “apolitical movement of angry citizens” as a way to gain more power. This has not gone entirely unopposed. The yellow vesters of Toulouse decided to evict Benjamin Cauchy from their movement due to his political views. On November 26, while invited at a radio show, the latter said that as an answer to his eviction, he was creating a new national organization entitled “Les Citrons” (the Lemons) to continue his fight against tax rises and took the opportunity to denounce the “lack of democracy that exists within the ‘yellow vest’ movement.”

Finally, it seems that the so-called “leaderless movement” completely changed its strategy in the aftermath of the second Parisian demonstration. On Monday, November 26, a list of eight official spokespersons of the movement was presented to the press. Apparently, the preceding day, yellow vesters were asked to vote online to elect their new leading figures. These nominations and strategic decisions are already creating tension within the movement. Some yellow vesters are now criticizing the legitimacy of the election, raising questions about how these leaders got selected in the first place.

Meanwhile, some members of the movement have called for another day of action on Saturday, December 1. The demands are clear: 1.) More purchasing power; 2.) The cancellation of all taxes on gas. If these demands are not granted, demonstrators say that “they will march towards Macron’s resignation.” So far, 27,000 persons have announced that they will participate in this event. Once again, the unity that was the watchword several weeks ago seems to have evaporated, as several local organizers have dissociated themselves from the movement in opposition to the more confrontational path that the movement seems to be taking.

A blockade by night.

Rather than addressing the question of horizontality, corporate media outlets have been focusing on another question: is the protesters’ anger legitimate?

Many media outlets have suggested that this movement is mostly composed of undereducated low-income people who are against protecting the environment; they describe the demonstrations as violent in order to delegitimize the anger of the participants. Despite this, some media outlets have shifted their discourse over time, becoming somewhat less condescending and more willing to broadcast demonstrators’ concerns. For example, after the confrontations at the Champs Elysées last Saturday, Christophe Castaner, the new Minister of the Interior, said: “the amount of damages is poor, they are mostly material ones, that’s the most important thing.” Quite a surprising statement, considering how corporate media outlets and politicians have decried similar actions during the demonstrations on May Day and the protests against the Loi Travail.

From our perspective, there’s no doubt that their anger is legitimate. Most people who take part in this movement speak of the difficult living situations they have to deal with every day. It makes sense that they are saying that they have had enough; the gas issue is just the straw that broke the camel’s back. The lower-class population has to struggle harder and harder to survive while everyone else remains comfortable enough not to be affected by economic shifts and tax increases targeting consumers. For now, at least.

So anger—and direct action—are legitimate. The question is whether the political vision and values that are driving this movement can lead to anything good.

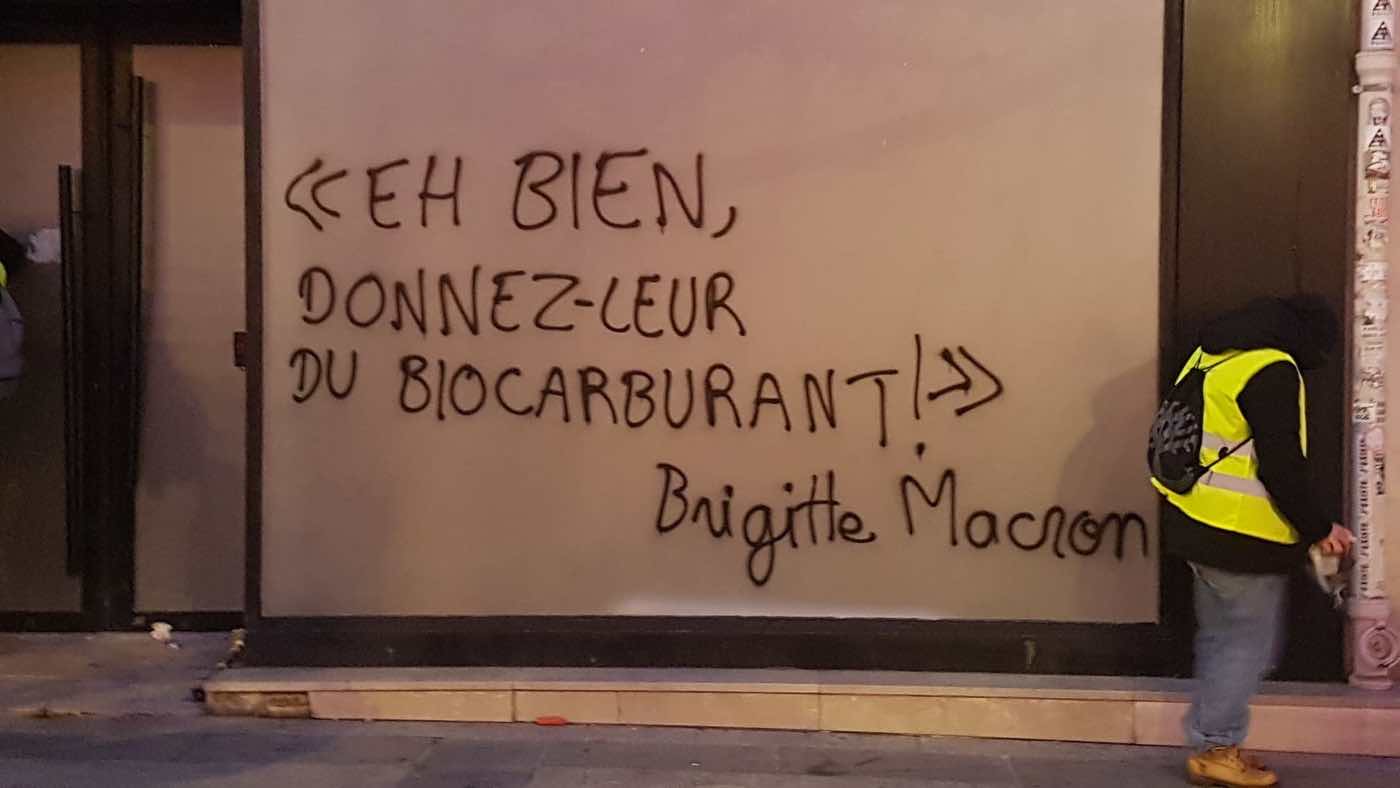

“Eh, let them eat biofuels - Brigitte Macron.”

Troubled Waters

Numerous racist, sexist, and homophobic acts have taken place during yellow vest actions. During the November 17 demonstration in Paris, several well known anti-Semites and nationalists were seen among the crowd of demonstrators. Members of far-right and nationalist groups participated in the demonstrations on November 24 in Paris, as well. Some comrades have reported that the presence of the far right in the Paris demonstration is “undeniable.” They describe seeing a group of monarchists with a flag; the crowd considered their presence “insignificant” compared to the water cannons that law enforcement used during the clashes.

The same report also mentions several elements that are difficult to interpret. For example, while the crowd in Paris chanted some classic slogans of May 1968 (“CRS SS”) and the Loi Travail demonstrations (“Paris debout, soulève toi!”), they also chanted the first verse of the Marseillaise, which is currently associated with traditional republican parties and the far right, not radicals. This chant could be understood as a reference to its origins in the French Revolution, but the song has been coopted by its role as the French national anthem, giving it a patriotic and nationalist tone.

Yellow bloc.

Another example: while marching down the Champs Elysées, the crowd chanted “We are at home.” For an English-speaking reader, this statement seems innocuous enough, an affirmation that the demonstrators had taken the streets, as the authors of the above report framed it. However, this chant echoes the one regularly used by National Front supporters during their meetings. Understood in that context, “we are at home” has a more sinister connotation. For nationalists, it means that France is and will always be a white, Christian, and nationalist country. Everyone who doesn’t fit their identity and political agenda is therefore considered a stranger or an intruder. In other words, this slogan creates a narrative about who belongs and who doesn’t. The use of these words during the yellow vest demonstrations is poorly chosen, if not ominous.

Paris is not the only place reactionary tendencies have emerged in the movement. Indeed, on November 17, in Cognac, yellow vest protestors assaulted a black woman who was driving a car. During the altercation, some protestors told her to “go back to [her] country.” The same day, at Bourg en Bresse, an elected representative and his partner were assaulted for being gay. In the Somme department, some yellow vesters called the immigration police when they realized that migrants were hiding inside a large truck stuck in traffic. The list goes on.

Finally, some participants in this “apolitical” movement have openly expressed contempt for social movements in general—including the movement for better education, the movement to defend hospitals and access to health care, and the movement of the railworkers. In effect, this movement that purports to dissociate itself from collective struggles so it can benefit “everyone” ends up promoting individualistic self-interest: the right of isolated consumers to keep using their cars however they want at a cheap price, without any real vision of social change.

Police block the freeway as yellow vesters make representations of themselves.

How Should We Engage?

Among anarchists and leftists, we can identify two different schools of thought regarding how to engage with the “yellow vest” phenomenon: those who think that we should take part in it, and those who think that we should keep our distance.

Arguments to distance ourselves:

-

The yellow vest movement claims to be “apolitical.” By and large, the participants describe themselves as disgruntled citizens who work hard but are always the first to suffer from taxes and government decisions. This discourse has a lot in common with the Poujadisme movement of the 1950s, a reactionary and populist movement named for deputy Pierre Poujade, or, more recently, with the “Bonnets rouges” movement (the “red beanies”).

-

The idea that the movement is “apolitical” is dangerous in that it offers a perfect opportunity for far-right organizers, populists, and fascists to insinuate themselves among protesters. In other words, this movement offers the far right a chance to restructure itself and regain power.

-

As soon as the movement gained widespread attention, extreme-right politician Marine Le Pen and other conservatives and populists expressed support for it. So much for the talk about being “apolitical”!

“The ultra-right will lose!”

Arguments in favor of participating in the movement:

-

This appears to be a genuinely spontaneous and decentralized movement involving low-income people. In theory, we should be organizing alongside them in order to fight capitalism and state oppression. Mind you, the concepts of class war and anti-capitalism are far from being accepted or promoted among the demonstrators.

-

Some argue that we should be participating in order to prevent fascists from coopting the movement and the anger it represents. Some radicals believe that we should take part in these actions as a way to make new connections with people and spread our ideas about capitalism and how to respond to the economic crisis.

-

For some radicals, being skeptical of the current movement and not wanting to take part in it can also indicate some sort of class contempt directed at the “apolitical” poor. Others argue that in every situation, we should always aim to be actors rather than spectators. Some even assert that if we are “true” revolutionaries, we should leap into the unknown and discover what is possible instead of passively criticizing from a distance.

All these arguments are valid, but if they lead to anarchists participating in a movement that offers fascists a recruiting platform—as some anarchists did in the Ukrainian revolution—that will be a disaster that opens the way for worse catastrophes to come.

“Down with the state, the police, and the fascists.”

The fundamental problem with the yellow vest movement is that it begins from the wrong premises, attempting to preserve conditions that we should all have been fighting to abolish in the first place. Rather than seeking to protect today’s alienated and miserable consumer way of life, which is itself the result of a century of defeats and betrayals in the labor movement, we should be asking why we are so dependent on cars and gasoline in the first place. If our ways of surviving and traveling had not been constructed in such an isolating, individualized way—if capitalists were not able to exploit us so ruthlessly—we would not have to choose between destroying the environment and giving up the last vestiges of financial stability.

We have to change our habits and give up our privileges in the course of fighting for another world (or another end of the world), but as always, governments and capitalists are forcing us to bear the brunt of the problems they caused. We must not permit them to frame the terms of the discussion.

“Overthrow Macron, disband the government, and abolish the system.”

Open Questions

Incidentally, the situation is quite different outside the French homeland. On the island of Reunion, since November 17, there has been a social upheaval in which all strategic sites have been blocked—the port, the airport, and the prefecture. Fearing that they might lose control of the situation and concerned about the impact on the economy, French authorities established a curfew on November 20 that lasted until November 25.

In Europe, as the yellow vest movement attempts to restructure itself after being weakened by leadership issues and conflicts over strategy, this might be an opportunity to create new bridges and make proposals about more systemic solutions to the problems that caused this movement.

Regarding ecology, we have to emphasize that the rich are the ones chiefly responsible for climate change, and that they will have to be the ones who pay to deal with it—if we are not able to dethrone them first. To some extent, this seems to be what the current blockading movement against capitalism and climate change, Extinction Rebellion, is trying to do in England. It is ironic that two different blockading movements about capitalism and ecology are taking place on either side of the English channel right now—one making ecological demands of the state, the other reacting to state environmental measures.

About nationalism, we must assert that it is no better to be exploited by citizens of our own race, gender, and religion than it is to be exploited by foreigners, and emphasize that we will only be able to stand up to those who oppress and exploit us if we establish solidarity across various lines of difference, including race, gender, religion, citizenship, and sexual preference. We are inspired by the yellow vest protesters in Montpellier who formed a guard of honor to welcome the feminist march on November 24.

Above all, we need an anti-capitalist, anti-fascist, anti-sexist, and ecological front within the space of social movements. The question is whether that should take place inside the “yellow vest” movement, or against it.

Chaos for Christmas.

There are so many dawns that have yet to break.